Clarity, Continental Philosophy, and the Cat in the Piano

Is clear writing good? Is it bad? Is it always?

What are we even fighting about?

Over the last few weeks on Substack, we’ve had a little three-and-a-half‑act drama about continental philosophy:

Act I: Bentham’s Bulldog posts “How Continental Philosophers ‘Argue’” – a viral rant arguing that continental philosophy is mostly vibes, jargon, and fake arguments.

Act II: Ellie Anderson replies with “Continental philosophy and the fetish for clarity” – sharing excerpts from a longer article that explores what “continental philosophy” means, arguing that “clarity” in analytic philosophy isn’t neutral, that continental philosophy has its own valuable tendencies, and that the job market is strangling them.

Act III: The Bulldog fires back with “Liking Clear Writing Isn’t a Fetish, Actually!” – doubling down on the virtues of clarity and accusing Anderson (and continentals generally) of changing the subject.

Then he adds a follow‑up, “Is Continental Philosophy Unclear Because the Subject Material Is Hard?”, which concedes he over‑generalized but doubles down on the idea that the field has all the “hallmarks of confusion.”

I’m not especially invested in who “wins” the quote‑Stack war. I am interested in what’s hiding underneath the fight:

What is clarity actually for?

When is difficulty a bug, and when is it (maybe) a feature?

I want to sketch a third position (possibly just Anderson’s position with cuter metaphors, but we’ll find out when she drops her full article):

I agree with the Bulldog that clarity is a real virtue, not just an analytic superstition.

I think Anderson is right that the norm of clarity comes with baggage, especially historically.

And I don’t think anyone is being particularly self-aware about how loaded their preferred style is.

But let’s start with the exciting part: the fighting.

Clarity as intellectual soap

Let us start by saying: clarity is good.

(Notice how the form matched the content? That’s going to come back.)

Clarity, in the sense we care about here, is not deep or morally pure. It’s more like… soap. Boring, indispensable, and mostly noticed when it’s missing.

When the Bulldog defends clear writing, he gives a decent list of what it buys you:

It lets readers actually see the argument instead of hallucinating one they like.

It makes subtle errors easier to detect and fix.

It’s simply less of a chore to read.

It makes it harder to hide confusion behind big words.

You don’t need a theory of truth to appreciate that. If you’ve ever tried to translate a 40‑line Derrida paragraph into plain English and discovered that half of it has fallen through your hands like dry sand, you already know why clarity matters.

Anderson’s pushback isn’t “clarity is bad,” it’s closer to:

“Hold on. Clarity isn’t neutral.”

In her post, she ties analytic clarity to things like:

the correspondence theory of truth (beliefs matching “states of affairs” out there),

a picture of language as a transparent window onto our mental states,

and a whole Descartes → positivism → logical empiricism pipeline that treats philosophy like math with better hair.

On the history, she’s right. Analytic philosophy really does inherit a dream that we can make thought precise, transparent, and math‑like.

(I love to do this myself, but being a political scientist by training, I usually need a lot of help with the mathy bits).

Anderson’s brief sketch sounds like she’s making this stronger claim, though I don’t actually think she is: that to embrace clarity is to buy into that whole metaphysical bundle.

But I think it’s pretty clearly possible to:

reject correspondence,

think language is messy, historically layered, metaphor‑soaked,

work on power, embodiment, and social construction,

…and still prefer writing where you can tell what the hell the author is claiming. Plenty of people do exactly that. I do that. And I don’t think it’s just because I’m admittedly a philosophically-untrained high-midwit.

Parfit wrote with extreme clarity, yet did not have a simple “belief aligns with atomic fact” picture of truth. Plenty of analytic philosophers are pragmatists, deflationists (hi!), or just deeply suspicious of heavy‑duty correspondence. None of that stops them from writing cleanly.

So yes: clarity has a history, and it isn’t innocent. But “I can understand this sentence” does not portend a right‑wing metaphysical coup. Clarity is a pragmatic norm about how we communicate, not a theory about what truth is.

Stripped of the bombast and overclaim, Bulldog’s basic position is pretty hard to argue against.

Now let’s bring in one of Anderson’s own citations, because it lets us keep both that claim and her suspicion.

Loaded clarity vs. default clarity

In her note, Anderson points readers to Nicholas Joll’s paper with the aggressively un‑clickbaity title:

“How Should Philosophy Be Clear? Loaded Clarity, Default Clarity, and Adorno.”

It’s a great reference because it basically does two things that matter here (whether or not Anderson herself would put it quite this way):

It formalizes her intuition that clarity is not self‑evident.

It salvages a minimal, non‑fetishized clarity we can still demand from everyone.

Start with Joll’s loadedness thesis: conceptions of clarity in philosophy are almost always philosophically partisan.

When you say “philosophy should be clear,” you’re usually also saying, more or less explicitly:

it should use certain kinds of arguments (logical, hypotactic, step‑by‑step),

it should aim at certain kinds of precision (definitions, necessary/sufficient conditions, no hand‑waving),

and it should down‑rank certain projects (poetic writing, emancipatory rhetoric, historically thick narrative, etc.).

In other words: “Be clear!” almost always smuggles in a view of:

what philosophy is,

what counts as a respectable method,

and what a real philosophical problem looks like.

That’s Joll’s loaded clarity. And it’s exactly the side Anderson emphasizes: the Adorno‑flavored suspicion that “clarity,” as wielded in analytic departments, is not neutral but ideological.

Anderson also points to Chapter 7 of Marcuse’s One‑Dimensional Man: the supposedly “clear,” “operational” language of advanced industrial society flattens contradictions and smooths away anything that doesn’t fit. Clarity, in that political sense, becomes a tool of control.

So far: team Anderson, team Adorno, team Marcuse.

But Joll doesn’t stop at “everything is loaded.” He also introduces “default clarity”—the part I really want to lean on, because it gives us a thin, cross‑tribal standard.

Very roughly, Joll’s default clarity has four pieces:

Explication of terms

If you’re going to lean heavily on a term that isn’t obvious, give it at least a provisional sense. Don’t introduce “hyper‑dialectical de‑phasing of the Other” and then never say what that means.Rigor

Make it possible to tell what your thesis is, and how you think you’re supporting it. It doesn’t have to be a numbered list, but don’t melt assertion, aside, metaphor, and conclusion into one dense block.

Precision (within reason)

Avoid ambiguity that actually matters to the claim. You don’t need set theoretic notation, but also you can’t be so vague that there’s no way of telling if you’re right, or even what would count as a counterexample.

Accessibility

Don’t make it way more technical than the job requires. Avoid gratuitous esotericism: unnecessary foreign phrases, “you had to be in the seminar” references, and purely ornamental jargon.

And then the crucial twist:

Default clarity is a default.

You can depart from it, but the burden of proof is on you to explain why.

This is the interesting middle position.

Joll backs Anderson in saying: stop treating clarity as self‑evidently good and content‑neutral; thick, scientistic “clarity” is tied up with specific philosophical and political commitments.

Joll also backs the Bulldog in saying: we still get to ask you to explain your key terms, show your argumentative spine, and not hide behind smoke.

Anderson understandably hammers the first point. She’s talking to an analytic‑heavy audience that treats clarity as obviously good and obviously theirs. My goal here is to pull the second half of Joll’s story into the same spotlight:

Even after you’ve de‑fetishized clarity and read your Adorno, you still want a notion like:

“You should be basically understandable unless you have a specific, defensible reason not to be.”

That’s the standard I’ll use for the rest of this piece.

Now we can ask the core question: when does it make sense to break default clarity?

When opacity might be justified

If I had to steel‑man the case for knowingly writing in a way that violates default clarity, it would look something like this.

Some philosophy is about reflexive domains:

language talking about language,

thought analyzing thought,

perception trying to catch itself in the act,

social orders interrogating the categories they themselves created.

In these domains, the tools of description are part of the thing being described. You can’t just “step outside” the system; you can only tear at it from within.

If you think that:

everyday language hides Being (Heidegger),

standard concepts stabilize what is actually fluid and contingent (post‑structuralism),

“clarity” itself can enforce “one‑dimensional” thinking (Marcuse),

“identity thinking” flattens what is non‑identical (Adorno),

…then using “normal,” smooth, transparent language to talk about how language isn’t smooth, or how concepts don’t fit their objects, looks suspicious. You risk reproducing the very patterns you’re trying to call into question.

So you:

coin new terms,

stress etymologies,

shift from neat hypotaxis (“if P then Q”) to parataxis (fragments in tension),

lean on aphorism, metaphor, juxtaposition.

That’s what Adorno is doing in Skoteinos: Or, How to Read Hegel. He’s not just saying “deal with it, Hegel is hard”: he thinks the classic Cartesian/positivist ideal of clarity:

assumes objects are static,

assumes concepts can be made perfectly sharp,

and wants philosophical language to behave like geometry.

If objects and concepts are historically moving, internally conflicted, socially mediated, then forcing them into geometrical, “clear and distinct” language is already a distortion. Better to write in dense constellations and essays and aphorisms than to lie.

So here’s my explicit “justified opacity” list:

Opacity may be justified when:

The target is reflexive (language, representation, conceptual schemes, subjectivity).

The phenomenon is structurally self‑undermining (you’re trying to show there is no fully stable meta‑language).

The aim is transformative disclosure rather than just propositional belief change.

You say what you’re doing: you actually give your reader a story about why the difficulty is part of the method.

That’s a pretty small and demanding set. It covers some Heidegger, some Adorno, some Derrida, some Blanchot, some Deleuze. It does not cover “I write like this because that’s how people in my department write and anyway I started this paragraph three jobs ago and now I have to hit ‘submit’.”

But before we concede the necessity of opacity, we should notice a striking fact from outside philosophy: some of the most conceptually disruptive art achieves its effect through jarring clarity.

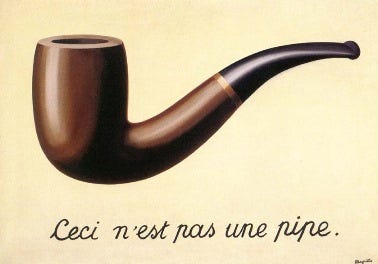

The Magritte principle

René Magritte, painting of a pipe, caption:

“Ceci n’est pas une pipe.”

“This is not a pipe.”

Surface:

child‑level French,

extremely clear image,

no visual or linguistic fog.

Effect:

instant destabilization of your naive picture of representation,

a little conceptual vertigo about signs and things.

Call this the Magritte principle:

Sometimes, disruptive depth requires a simple surface.

Magritte does, in one glance, what a lot of dense semiotics tries to do in a chapter. Hopper does Sartre‑level existentialism in a single stark diner scene. Turrell does Merleau‑Ponty on visibility with a glowing room.

Now, to be fair: philosophy is not art. It owes us:

actual inferences,

some propositional content,

some sense of what would count as being wrong.

Magritte doesn’t have to give you a rebuttal to a rival semiotic theory. Heidegger and Adorno do.

But as a model of how form and content can work together, the Magritte principle is powerful:

It shows you don’t have to be obscure to be disruptive.

It shows how far you can get with clear language and a clever frame.

It sets a bar: if your philosophical text can’t do any of that work clearly, you’d better have a very good story about why.

It certainly seems that we have lots of Magritte‑like possibilities for philosophy that we simply haven’t built out, because the incentive structures in parts of the continental world are stuck on “dense is deep.”

So if clarity can destabilize, what does earned difficulty actually look like?

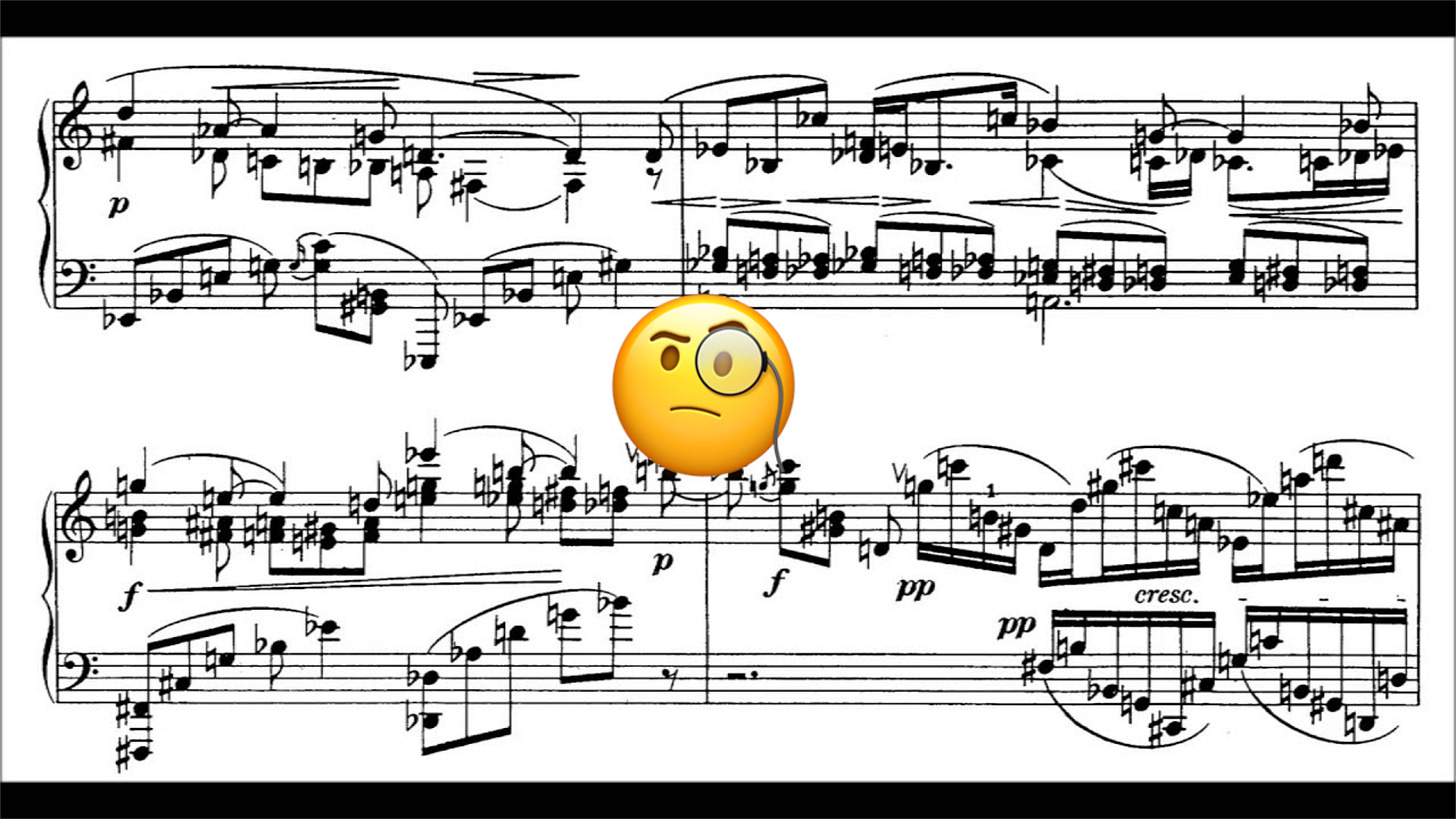

Atonal music, atonal prose

If Magritte gives us the case for clarity-with-depth, atonality gives us the best case for difficult form-without-bullshit.

Tonal music has a grammar:

keys,

cadences,

tension → resolution,

stable centers.

Break that grammar aggressively and, to most ears, the piece stops sounding like “music” and becomes just… sound. The archetypal cat loose in the piano. Atonal composers know this. They are intentionally breaking the tonal system in order to:

get at intervals and structures tonality hides, or

express kinds of tension and release the old grammar can’t easily carry.

There’s intentional atonality (Webern), accidental atonality (random noodling), and atonality that relies on external scaffolding (Cage’s 4′33″: the point is the frame).

A lot of continental writing is basically doing the same thing with prose.

Ordinary discursive prose has its own “tonal” grammar:

straightforward sentence structure,

clearly flagged premises and conclusions,

settled distinctions (subject/object, inside/outside, word/thing),

the familiar “first we define, then we argue, then we conclude” arc.

Draw inside those lines and you sound intelligible by default. But if you think that very grammar is part of the problem, you might:

break the syntax,

re‑purpose words,

write in fragments,

let multiple voices collide in the same text.

At their best, those maneuvers are trying to be intentionally atonal: formally weird, structurally disciplined, aiming at a different kind of intelligibility.

At their worst, they’re just noodling: difficulty with no discernible structure, no clear sense of necessity, no explanation.

So:

Intentional atonality and good “opaque” prose both do violence to a grammar in order to show the grammar’s limits.

But here’s the catch:

Music’s grammar is its essential skeleton. Philosophy’s grammar isn’t.

If you stay tonal, you are staying inside that system. Music really does need to break its internal grammar to get certain effects.

Philosophy isn’t as constrained. Its medium is natural language, which is wildly flexible; it can be:

discursive,

poetic,

narrative,

fragmentary,

technical,

funny.

We absolutely can write things that:

read smoothly,

and still leave your mental furniture upturned by the end of the page.

Joan Didion does this. Simone de Beauvoir does this. Foucault, in some of his more historical work, does this. Even Hegel, chaos muppet that he is, has passages in the Phenomenology preface where he just… says what’s wrong with previous philosophy.

Which takes us to the flip‑side.

When opacity is just bad

If we’re going to be fair, we need to name unjustified opacity just as explicitly as justified opacity.

Here’s my list:

Opacity is not justified when:

The core theses could be stated plainly, but never are.

There’s no attempt to say why the text is difficult; it’s just treated as a mark of depth.

Every attempt at second‑order clarification (teaching, commentary, “for a general audience” essays) is also opaque.

The difficulty mostly tracks sociological incentives: publish‑or‑perish pressure, prestige norms, the “10–20% incomprehensible” culture Foucault jokes about.

The supposed “depth” evaporates when you ask, in simple language, “OK, what follows from this? What would count as a counterexample?”

On this standard, a lot of continental philosophy really does have a legibility problem. Not because the ideas are deep, but because the prose is allowed to be bad without cost.

This is legibility debt:

Analytic philosophy has high, enforced legibility norms: if you can’t give the two‑sentence version of your view in a Q&A, someone will do it for you and then kill it.

Continental philosophy has variable, often weak legibility norms: some writers are perfectly lucid, others are rewarded for being unreadable to anyone outside a very specific interpretive community.

Over decades, this builds up as deferred explanation: “It will all make sense if you read Hegel’s entire corpus and then my four favorite commentators and also live in Paris for a bit.”

Analytic philosophy pays its legibility bill up front; continental philosophy often kicks it down the road to commentaries, seminars, and insider culture. Default clarity is Joll’s way of saying: the bill is eventually due.

Where the Bulldog overreaches

Back to Bentham’s Bulldog.

There are points where he’s just right:

Some continental prose is the textual equivalent of Albertan tar sands.

Fields with low standards of clarity do attract charlatans.

If you strip away 80% of the jargon from certain paragraphs and discover a truism or a mistake where the profundity was supposed to be, that’s… not great.

But he also overplays his hand in ways that make it too easy for continentals to shrug him off.

1. “Continental philosophers don’t really make arguments”

This is like saying “jazz musicians don’t really play melodies.”

They do; they just disassemble them, warp them, bury them in improvisation.

Continental texts do contain arguments:

Phenomenology gives structured descriptions meant to support claims about intentionality, embodiment, perception.

Foucault’s genealogies make explanatory claims: “Here’s how this practice came to look natural; here’s what it does.”

Even Butler—Bulldog’s favorite piñata—is usually stitching together premises about discourse, the body, and power into something that looks a lot like an argument.

Are those arguments always premise → conclusion in numbered form? No. Are they sometimes unclear, under‑argued, or dressed in ridiculous clothes? Yes. But of course “hard to reconstruct” does not mean “nonexistent.”

The “for Beauvoir, P” tic he mocks (“for Beauvoir, women are…”), while grating, isn’t meant to prove P. It’s shorthand for:

situating the claim in a lineage,

flagging that we’re inside a certain conceptual apparatus,

not claiming to be reinventing the wheel.

Analytic folks do the same with “as Lewis shows…” and “following Rawls…”

2. “Continental philosophers think reality is subjective”

Bulldog quotes Foucault on “regimes of truth,” Berger & Luckmann on social construction, and comes away with something like: “These people think there are no facts, only beliefs. RIP dinosaurs.”

But for most of these thinkers, the move isn’t:

“There wasn’t really a world before us.”

It’s:

“The way we carve up that world — into kinds, categories, identities, ‘pathologies,’ ‘perversions,’ ‘normality,’ etc. — is historically contingent and bound up with power.”

You can argue with that. You can say they overgeneralize, conflate ontology and epistemology, or underplay the stability of some categories. But “they think reality is just vibes” is a strawman.

“Sexuality is socially constructed” is not “nothing is real.” It’s “this concept, and the roles/institutions clustered around it, did not fall from the sky.”

3. “If you can’t explain it simply, it’s nonsense”

In both his original and his follow‑up, Bulldog leans on a Chomsky‑style rule:

real sciences are hard but can be explained to a smart undergrad,

Derrida cannot,

therefore Derrida is nonsense.

Tempting. Too quick.

Some things really are harder to explain because they’re reflexive or structurally weird:

they’re about the limits of representation,

or about self‑defeating pictures,

or about background practices we normally don’t notice.

Late Wittgenstein is not exactly a /r/explainlikeimfive thread either, and yet he survives the “nonsense” test just fine.

A better rule of thumb:

If nobody ever manages to make your stuff clearer—not in teaching, not in commentary, not in a slower second book—then yes, something is probably wrong.

Continental philosophy absolutely has texts like that. It also has the more common pattern:

“atonal” originals,

plus “tonal” secondary literature that does make them more tractable.

This puts us back in “legibility debt” territory, not “everything is fake.” I still think a lot of continentals could try harder on the tonal side themselves. But “I bounced off it” is not a proof of vacuity.

Where Anderson could go further

On the other side, Anderson is doing several useful things:

She’s right that “continental philosophy” is a historically contingent label, largely constructed as analytic philosophy’s other.

She’s right to point out the stark material asymmetry: the cited 10x discrepancy between tenure track jobs for philosophy of science versus all of continental philosophy is pretty wild.

Her “grafting vs. ground‑clearing” metaphor is great: analytic philosophers like to clear conceptual space and rebuild from minimal premises; continentals like to graft new concepts onto old rootstock (Husserl + Beauvoir + Austin → Butler’s “performativity,” etc.).

I’m very much on board with all of that.

Where I think her reply doesn’t go quite far enough is in two places:

1. Clarity vs correspondence theory

In her sketch, Anderson ties analytic clarity to the correspondence theory of truth and to an idea of language as directly expressing mental states. She notes that Heidegger, Nietzsche, Adorno, etc., are suspicious of these assumptions, and so, in her telling, suspicion about those assumptions naturally bleeds over into suspicion about the norm of clarity itself.

This is where Joll’s distinction helps:

We can grant that loaded clarity—the full Cartesian / positivist package—is metaphysically suspect.

We can still keep his default clarity as a thin, pragmatic norm: explicate your crucial terms, make your argumentative spine visible, avoid gratuitous vagueness and jargon.

Anderson is absolutely right to attack the loaded kind. But that doesn’t, by itself, undercut the default kind.

2. Owning the obscurantism problem

Anderson acknowledges that some of the vices the Bulldog identifies are real; she even pulls the 1999 Nussbaum article that contains the iconic line,

It is difficult to come to grips with Butler’s ideas, because it is difficult to figure out what they are.

But the overall emphasis of the excerpt is understandably one‑sided: clarity is loaded, continental philosophy is marginalized, analytic folks often don’t get its aims.

All of that is true. But from the outside, it can sound a bit like:

we’re misunderstood,

the job market is unfair,

and anyway your clarity is ideological.

A stronger stance, to my ear, would be:

Hey, the job market is brutal and structurally biased toward analytic norms,

and thick, scientistic “clarity” has often been used to police boundaries and exclude certain projects,

and also, we have a genuine obscurantism problem. Some of our writing really is unjustifiably opaque.

That last point doesn’t concede the Bulldog’s “unseriousness of the discipline” tantrum. It just takes Joll’s burden‑of‑proof move seriously: if you’re going to depart from default clarity, you owe your reader at least a sketch of why.

To be fair, Anderson herself says the excerpt’s main job is to map and motivate continental tendencies, not to offer a knock‑down defense of them. I’m using her sketch as a jumping‑off point, not treating it as a full argument for or against clarity.

Two different jobs for words

Here’s a common framing that keeps me sane when reading both styles.

Very roughly:

Analytic philosophy treats natural language as a slightly messy interface to thoughts that could, in principle, be expressed in a more formal way: logical notation, math, decision procedures. Words are the GUI for a deeper system.

Continental philosophy (in its more radical strands) treats natural language as the irreplaceable medium of thought. Metaphors, etymologies, resonances, and ambiguities are not noise; they’re where the action is.

On this picture:

The analytic ideal is to make philosophy more like math or science.

The continental ideal is to make philosophy more like poetics or art.

Not “one has arguments, the other has vibes.” More like:

one privileges propositional justification,

the other privileges phenomenological / historical / affective disclosure.

They answer “what are words for?” differently.

If you buy that, then:

The Bulldog is basically saying: “Stop using words like paints and use them like proof trees.”

Anderson is basically saying: “Stop pretending your neat sentences and symbols are neutral; they already encode a view of reality.”

And Joll’s default clarity sits right in the overlap:

Regardless of whether you’re doing math‑ish philosophy or art‑ish philosophy, you can still:

say what your key terms mean (for now),

say what you’re actually claiming,

give some sense of how that claim is supported or enacted.

After that, go wild. Write your atonal symphony. Just don’t confuse “I made it hard” with “I made it profound.”

So… what do we do with all this?

Here’s where I land.

Clarity is a virtue, not a fetish.

If I can’t tell what you’re saying, I can’t tell whether it’s true or interesting. If nobody outside your subfield can tell, you have a quality‑control problem, not an aura of depth.Some difficulty is structural—but probably less than advertised.

Reflexive, self‑undermining projects really do strain language, and some weirdness is inevitable there. But we are currently running a good amount of unnecessary friction under the banner of “this is just how deep thought sounds.”Continental philosophy has real value and a real legibility debt.

Questioning “common sense,” doing genealogy, grafting new concepts onto old ones—these are important. They also desperately need more Magritte‑style exposition: simple surfaces, disruptive depths.Analytic philosophy’s norms aren’t neutral, but they aren’t fake either.

The demand to spell things out is not just a power‑play; it’s also basic intellectual hygiene. At the same time, analytic philosophers should stop pretending their favorite kind of clarity fell out of the sky. It has a history and a politics.We should adopt something like Joll’s “default clarity” as a shared minimum.

Explicate important terms.

Distinguish thesis from support.

Avoid avoidable ambiguity and unnecessary jargon.

Don’t make your work more inaccessible than the content genuinely demands.

If you break these, you owe us—not a 50‑page confession—but at least a paragraph of “here’s why I’m departing from the usual norms.” And if you don’t at least lampshade it, don’t be surprised if people outside your intellectual inner circle don’t give you the benefit of the doubt.

We should aim for “atonal when necessary, tonal whenever possible.”

Let the hard, twisty, structurally weird passages earn their keep. Surround them with writing that doesn’t make people feel like they’re wading through wet cement.

Joll gives us the skeleton: a distinction between loaded clarity and default clarity.

Magritte shows that clarity can be radical, that simple surfaces often do fantastically destabilizing work.

Atonality reminds us that difficulty has a place—but only when the form must contort to reveal what the normal grammar hides.

Ultimately, I’d like a philosophical world where:

you can do serious work on language, power, embodiment, or history

without being forced into three layers of jargon just to be taken seriously,

and without being told that anything less than symbolic logic and a truth table is unserious.

That world is not utopian. Magritte managed something like it with a pipe and a caption. A lot of artists manage it every day with their own tools. It seems to me there is no deep reason philosophers can’t do the same.

Until then, we’re stuck in this slightly absurd situation where:

one side yells “Stop worshipping clarity!”,

the other yells “Stop worshipping obscurity!”,

and both, in their own way, dodge the more boring, more difficult work:

Actually writing philosophy that is as clear as it can be,

and only as difficult as it has to be.